At the time it was being built, many people were dissatisfied with the design for the Peace Palace exterior by Louis Cordonnier; he designed a Renaissance building with gothic elements, made out of brick and natural stone with sculptured ornamentation such as pilasters and friezes. The public felt the traditional design-aesthetic harked back to old ways of thinking, which had led to war, rather than being a visual representation of the hope for a modern, peaceful society. Herman Rosse was able to bridge the gap between past and present in his style of design for the interiors of the building. But where did he get his inspiration to bring the Peace Palace into the twentieth century?

The designers behind the great artworks of the Peace Palace are part of a new research project by the Carnegie Foundation. Amongst these designers was Herman Rosse – the youngest, least-experienced of them all – yet his artworks cover the largest surface area of the building. His work here was the start of a wondrous career that would lead him to an Oscar. We followed his tracks, from several archives to his children, to find out more about the man behind the most impressive artwork of the Peace Palace.

At the time it was being built, many people were dissatisfied with the design for the Peace Palace exterior by Louis Cordonnier; he designed a Renaissance building with gothic elements, made out of brick and natural stone with sculptured ornamentation such as pilasters and friezes. The public felt the traditional design-aesthetic harked back to old ways of thinking, which had led to war, rather than being a visual representation of the hope for a modern, peaceful society. Herman Rosse was able to bridge the gap between past and present in his style of design for the interiors of the building. But where did he get his inspiration to bring the Peace Palace into the twentieth century?

The Arts and Crafts Movement

By the late-1800s, the Industrial Revolution had been rolling out to many countries across the globe. However, some artists were resistant to the de-personalization of artwork that accompanied this new mass production.

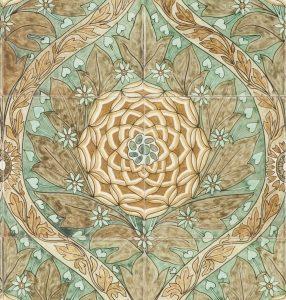

Instead of true-to-life art featuring flora and fauna there was a switch to more simplified line work, designs and geometric patterns. This was known as the Arts and Crafts movement, an idealistic movement which believed that being surrounded by beauty would morally enrich mankind – so they applied their art to interiors, furnishings and utensils. The movement had one foot in the present and the other grounded in the past and was a way of counterbalancing the Industrial change by combining both traditional and modern styles.

Embarking on his life of adventure at only eighteen years old, Herman’s first stop along his journey took him to the Royal College of Arts in 1905. The Arts and Crafts movement already dominated this London-based school and, having been inspired by the movement from his Holland education, Herman’s interest was compounded. This is where he studied under the great proponents of Arts and Crafts, William Lethaby, and apprenticed to Charles Voysey – a famous English architect and decorator whose great oeuvre is still inspirational today.

An Influence on Herman’s Style

Whilst studying Architecture and Design at the Royal College of Arts, Herman also worked in Charles Voysey’s studio. Voysey never employed a large staff of assistants and so the environment was intense. His pupils were tasked with making copies of his work and so his style would have naturally crept into their own designs through sheer repetition under such concentrated working conditions. Evidence of this can be seen in Herman’s own work too when we compare it with his mentor’s. Though designing in a minimalist style was fashionable at the time, the line-work of Herman and Voysey is modern and bold, both typically using solid blocks of colour in their geometric patterns. Combining modern art techniques with natural elements such as flowers, leaves and thorns creates a stylized image: bold, clean and almost unreal because the depiction of nature don’t imitate real life and instead seems almost fantastical.

Making the impossible a reality was something which Herman excelled at and it is something which would become an essential part of his later career when he designed, not only the Peace Palace, but also costumes and sets for films. Over the years, he and Voysey developed a warm friendship and Voysey considered Herman to be a star pupil. Not only was he instrumental in the development of Herman’s style but may also have been the one to recommend him as the ideal designer for the Peace Palace at only 24 years old.

Bridging Gaps

By implementing a style that refers to the Arts and Crafts movement Herman, in a way, bridged a gap between the past and the present in the Peace Palace. He somewhat modernized the traditional aesthetic of Cordonnier by using this combination of old and new design motifs and helped pull the building firmly into the twentieth century. The combination of exterior and interior designs cemented the building as the visual representation of a move towards the hope for a more peaceful future.

Not only did Herman unite past with present, his designs simultaneously bridged the gap between cultures by using motifs that crossed cultural divides – the abundant baskets of flowers and, above all and perhaps most importantly, the use of bright colours unite people of the whole world with their paradisical connotation. This cultural and chronologic unity was aspirational because it embodied the peace between people and countries which the Peace Palace strove for at the turn of the new century.

Would you like to learn more about the interior design of the Peace Palace? Guided tours are run regularly and you can visit the Visitors Centre during these times, there you can find a special magazine about Herman Rosse and his decorations is available in our webshop and in our Visitors Centre.