The 'biography' of the Ghent Altarpiece, also called the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, reads like a thriller. From the beginning this fascinating work was the object of passionate desire to either possess or destroy it. During the centuries of its existence, the altarpiece witnessed religious upheavals in the Southern Netherlands, came close to being destroyed during these outbreaks of iconoclasm and was damaged when moved to save guard it or when stolen. It endured fires, Napoleon’s looting army and two world wars. Parts of it were stolen, burned, recovered and stolen again and again.

Article 247, second clause, of the Treaty of Versailles, signed in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, Paris, in 1919 between Germany and the Allied Powers stated:

“Germany undertakes to deliver to Belgium, through the Reparations Commission, within six months of the coming into force of the present Treaty, in order to enable Belgium to reconstitute two great artistic works:

1. The leaves of the triptych of the Mystic Lamb painted by the Van Eyck brothers, formerly in the Church of St. Bavon at Ghent, now in the Berlin Museum;

2. The leaves of the triptych of the last Supper, painted by Dierick Bouts, formerly in the Church of St. Peter at Louvain, two of which are now in the Berlin Museum and two in the Old Pinakothek at Munich.”

The panels of the Mystic Lamb were returned to Ghent in 1923, almost five hundred years after its completion in 1432. A specially prepared train, decorated with Belgian flags brought the 6 panels back to Belgium. The national treasure returned like a wounded war hero and was met in every Belgian city where the train passed by large crowds, chimes of Church bells and the tunes of the Brabançonne, the national anthem of Belgium. The diaspora of the panels was over; once again they were united with the other 6 in their original birthplace, the Vijd Chapel at the Saint Bavo Cathedral. It was whole once more, only to be stolen again and again till in 1946 the painting finally returned to Ghent.

The “biography” of this magnificent work of art, the first major oil painting in history, reads like a thriller. From the beginning this fascinating work was the object of passionate desire to either possess or destroy it. During the centuries of its existence the altarpiece, this iconic painting, one of the world’s greatest masterpieces witnessed religious upheavals in the Southern Netherlands, came close to being destroyed during these outbreaks of iconoclasm and was damaged when moved to save guard it or when stolen. It endured fires, Napoleon’s looting army and two world wars. Parts of it were stolen, burned, recovered and stolen again and again.

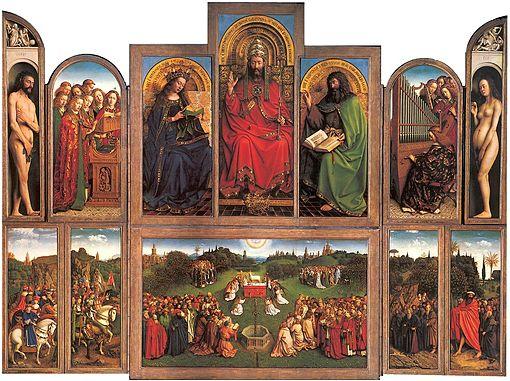

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb designed by Hubert van Eyck but largely painted by Jan van Eyck who, though indebted to the medieval tradition and religious themes, concentrated on the exacting observation of nature. The artistry and realistic detail was unparalleled for centuries to come. The clothes and jewels, the fountain, nature surrounding the scene, the churches and landscape in the background were painted with remarkable detail and accuracy. Jan van Eyck used new oil paint techniques the world had never seen before. How he mixed the paint to create an inner radiance is still unexplainable even with the modern techniques of today. He layered the paint in a way that gave it a translucent iridescent effect that mesmerizes the onlooker. The painting is filled with secret spiritual messages and legend has it that possession of the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb with the Fountain of Life will give the owner eternal life. This impressive enormity of qualities gave this painting the status and lure of a superstar today, and was the pinnacle of desire throughout the ages for Kings, Emperors, common villains and the Führer. The Kaiser ordered his men to find the hidden panels in German occupied Ghent, but they failed.

Its tumultuous history made another dramatic turn when article 247 of the Peace Treaty of Versailles (1919) ruled that six panels of this painting were to be handed over to the Belgian authorities. These panels, although once stolen from the Ghent Cathedral were eventually legitimately bought by the Prussians, and were in the possession of the Kaiser Friedrich museum in Berlin. They were designated by the Restoration Commission as German compensation for the loss and damage of works of art due to German military operations and misbehavior on Belgian soil. Exemplified by the destruction of the Library of Louvain and the burning of important manuscripts, books and incunabula. Article 247 of the Versailles Treaty and the return of the altarpiece was an “innovative step in international law”. See Kurtz, M.J., America and the Return of Nazi Contraband: the Recovery of Europe’s Cultural Treasures, pp. 8-9.

“The Germans were ordered to provide restitution-in-kind to Belgium for the destruction in Louvain. Here for the first time was articulated a requirement to reintegrate works of art into a nation’s historical and artistic heritage. It was not looted but legally required in German possession. The return stirred bitter German resentment and destined to be looted again would well fit into the nazist racist view of art history. The Allies established the principle of using works of art as reparations (i.e. compensation for other, destroyed works of art). In requiring reparations for cultural losses, the Allies determined that legitimate purchases could be voided and that public collections of the defeated were fair game. These measures and the one that mandated restitution for an earlier conflict provoked a fierce German reaction, which manifested itself in the next war and would also complicate restitution efforts after that conflict”.

Not for long, in 1934 two panels of the famous work were stolen, only one returned. The whereabouts of the other long lost lower left panel - is to this day - still shrouded in a mysterious fog of possibilities.

For Herman Göring and Adolf Hitler the Ghent Altarpiece was their most coveted trophy. They tried to outmaneuver each other to possess it. Aside the painting’s cultural importance and exceptional beauty rumor has it that Hitler, fascinated by the occult, was convinced the painting contained a coded map to the so-called Arma Christi, or instruments of Christ’s Passion, the Crown of Thorns and the Spear of Destiny. Hitler believed that possession of the Arma Christi would give its owner supernatural powers. He ordered the painting to be seized and brought to Germany. After an incredible itinerary from the Pyrenees to Paris, being on the way to Neuschwanstein Castle in the Bavarian Alps, which was prevented by the threat of Allied bombardments, the painting eventually ended up in an Austrian salt mine in Alt Aussee. There it was recovered with thousands of other artistic masterpieces in an underground storehouse by American soldiers. (read: Robert M. Edsel, The Monument Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History, London, 2010.)

Many important authors wrote extensively about means to stop the destruction, looting, pillage and stealing of enemy property, public monuments, temples, tombs, statutes, paintings. In the seventeenth century it was Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) in his De iure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace) in 1625, Book III, Chapter V. On the right to lay waste an enemy’s country, and carry off his effects, referring to ancient authors like Cicero, Polybius and Ulpian. Emerich de Vattel (1714-1767) in The Law of Nations, 1758, III, Chapter 9, Section 168, Henry Wheaton (1785-1848) in Elements of International Law, 1836, section 347, and later Henry Wager Halleck (1815-1872) in his International Law or Rules Regulating the Intercourse of States in Peace and War, 1861, ch. xix, sections 10-11. Legal regulations, such as the Lieber Code/Instructions for the Governance of Armies of the United States in the Field, 1863, compiled by Francis Lieber (1800-1872), the Brussels Declaration of 1874, the Oxford Manual of 1880 and the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, could not prevent the hunt for cultural property.

In the twentieth century, international criminal tribunals were vested with jurisdiction over war crimes, including ‘plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity’. It remains to be seen if this will be a guarantee for a quiet and safe life of the Mystic Lamb.

- Davis, G.B., "Doctor Francis Liebers’ Instructions for the Government of Armies in the Field", 68 American Journal of International Law, (1907), pp. 13-25.

- Merryman, J. H., "Cultural Property Internationalism", International Journal of Cultural Property, 12 (2005), pp. 11-39.

- Grotius, H., De iure belli ac pacis libri tres: in quibus ius naturae & gentium, Paris, 1625.

- Halleck, H.W., International Law or Rules regulating the Intercourse of States in Peace and War, New York, 1861.

- Kervyn de Lettenhove, H., La guerre et les oeuvres d'art en Belgique, 1914-1916, Bruxelles, Van Oest, 1917.

- Kurtz, M.J., America and the Return of Nazi Contraband: the Recovery of Europe’s Cultural Treasures, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Lieber, F., Lieber's Code and the Law of War, Chicago, Precedent, 1983.

- O'Keefe, R., "Protection of Cultural Property under International Criminal Law", Melbourne Journal of International Law, 11 (2010), pp. 1-54.

- Petrovic, J., The Old Bridge of Mostar and Increasing Respect for Cultural Property in Armed Conflict, Leiden, Nijhoff, 2013.

- Van den Gheyn, Les tribulations de l’Agneau mystique, Anvers, 1945.

- Vattel, E. de, Le droit des gens, ou Principes de la loi naturelle, appliqués à la conduite et aux affaires des nations er des souverains, Londres, 1758.

- Visscher, F.Ch. de, International Protection of Works of Art and Historic Monuments, Washington, DC, Department of State, 1949.

- Visscher, C. de, "La protection internationale des objets d'art et des monuments historiques: 1: La conservations du patrimoine artistique et historique en temps de paix", Revue de droit international et de législation comparée, 62 (1935), pp. 32-74.

- Visscher, C. de, "La protection internationale des objets d'art et des monuments historiques: 2: Les monuments historiques et les œuvres d'art en temps de guerre et dans les traites de paix", Revue de droit international et de législation comparée, 63 (1935), pp. 246-288.

- Wheaton, H., Elements of International Law, Philadelhphia, PA, Leal and Blanchard, 1846.