Deir az-Zor is a sleepy town on the banks of the Euphrates in the Syrian desert, and did not ring much of a bell for most non-Syrians. Except for Armenians. During the 1915 Armenian Genocide, the Ottoman government deported hundreds of thousands of Ottoman Armenians to Deir az-Zor, where they were left to die or were killed outright. A German diplomat who was stationed in that area wrote that the Armenians were “slaughtered like sheep”. To the casual observer this looked allegorical or even hyperbolical, in any case unreal, removed far away in geography, time, and culture. Until recent times, when ISIS videos surfaced online. And again the desert soil of Deir az-Zor shone red with blood, and once more the word ‘Deir az-Zor’ served as a symbol of bloodshed.

This blog has been written by Uğur Ümit Üngör, Associate Professor at Utrecht University and researcher at the Dutch Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (NIOD)

Deir az-Zor is by no means an isolated case in the current Syrian-Iraqi catastrophe. Palmyra, Raqqa, Kobanî, Aleppo, Mosul, and many other cities and the spaces in between have seen very high levels of violence, both between armed groups and against civilians. In fact, never before have we witnessed this type of implosion of the state and the collapse of societal coexistence in this region. Conservative estimates place the death toll of post-2003 Iraq at 200,000 and that of the ongoing Syrian cataclysm at 400,000. These figures offer only a glimpse of the profound social, economic, and psychological damage inflicted on the Syrians and Iraqis across generations. What are the causes and consequences of these conflicts? How are these conflicts interrelated, politically, culturally, chronologically, and theoretically?

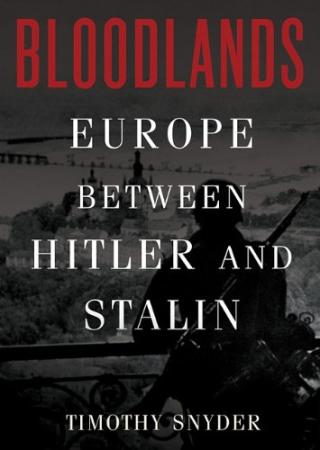

Bloodlands of the Middle East

The famous book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Eastern Europe expert Timothy Snyder might offer some comparative insights. In this book, Snyder argues that the destruction of human lives between the years 1933 and 1945 can be explained partly by the interaction of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in that period. More importantly, the most lethal violence against civilians can be understood best in terms of statelessness. As the Nazis and Soviets proceeded to occupy the lands between Berlin and Moscow, they destroyed existing state structures and therefore experienced no resistance against their murderous policies. Consequently, they also offered a political space in which various political groups could implement their ideological and violent agendas.

Whereas Snyder’s interpretation has been criticized, his ideas are remarkably applicable to Syria and Iraq, especially the lands between Damascus and Baghdad. Both states are relatively young, both societies have similar compositions, both fought a set of destructive wars with neighbors (Israel and Iran, respectively), both are surrounded by larger powers with strong interests (Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia), and both have similar institutions. But only in conditions of utter statelessness and lawlessness could an extremist group like ISIS seize power and impose their extreme ideology on the hapless remnants of those two societies. But what are the deeper historical and political contexts of all of this violence? Are we dealing with coincidences, repetitions, interactions, continuities, transformations, or otherwise? We have only begun to scratch the surface of these questions.