"125 years ago, diplomats, lawyers, military experts, and peace activists gathered in The Hague for the First Hague Peace Conference. At the meeting, they laid the foundation for today’s international courts and tribunals and agreed on new treaties, which led to the reputation of The Hague as the city of peace and justice. In a new book, I tell the tale of the conferences and how they shaped The Hague and the modern world order."

Benjamin Duerr is a German-Dutch international lawyer, diplomat, and writer.

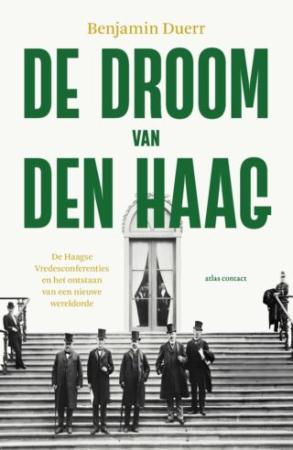

During a celebration to mark 125 years of peace and justice in The Hague in May, the mayor of The Hague, Jan van Zanen, will receive the first copy of the ‘Droom van Den Haag: De Haagse Vredesconferenties en het ontstaan van een nieuwe wereldorde’. Representatives from government, the peace movement, and others will share their perspectives on the history, present and future of peacebuilding.

When the governments of Russia and the Netherlands announced they would organise an international conference in the summer of 1899 in The Hague, the world reacted with surprise. Not only the points on the agenda, such as the limitation of armaments and the establishment of multilateral procedures to resolve disputes, appeared illusionary. The place where the conference was to take place, too, was rather unconventional.

Until late in the nineteenth century, The Hague was considered a rather sleepy town, known mainly because of the seat of the royal court, but largely irrelevant in international affairs. The British envoy to the Netherlands in the 1880s and 1890s, Sir Horace Rumbold, wrote in his memoires rather diplomatically that The Hague was of ‘interesting though not of an absorbing nature’, and ‘essentially a poste d'observation’.

However, with the opening on 15 May 1899 of the congress, which became known as the First Hague Peace Conference, the history of The Hague, of diplomacy, and of international law changed for good. Representatives from 26 states discussed proposals for a limitation of armaments and the prohibition of certain types of weapons; they agreed, for the first time, on binding rules on warfare; and they decided to create the Permanent Court of Arbitration to provide states with an instrument to settle their disputes peacefully.

When a second conference was convened in 1907, even more states were represented and by then The Hague had become a well-known city of hope and aspirations. Across town, congresses were held in parallel to the formal negotiations. The Hague attracted activists who sought support for a Jewish state, wanted to draw the world’s attention to the violence against Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, and demanded the independence of Congo.

My new book, ‘De droom van Den Haag’ (‘The Dream of The Hague’), takes readers to the different places where people from around the world developed their ideas for peace and justice. It shows how, within a few years, The Hague developed a global reputation that still persists today. I tell the story of the Hague Conferences through the eyes of four main actors who represent the larger movements and concepts.

The Russian lawyer Friedrich Fromhold Martens was intimately involved in the preparations and the negotiations. At the 1899 conference, he drafted as a compromise a treaty article which became known as the Martens Clause and is until this day considered as a crucial element of international humanitarian law. The Austrian writer and peace activist Bertha von Suttner held dinners for select groups of participants in her hotel and gave numerous public lectures. She hoped the Hague Conferences would contribute to the abolition of war and represented the ideas of the peace movement. The Dutch minister of foreign affairs, Willem Hendrik de Beaufort, constantly tried to navigate domestic public opinion and international ambitions. American naval officer and strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, on the other hand, sought to prevent agreement on rules too strict to not limit the growth of the United States as emerging great power.

In The Hague in 1899 and 1907, the visions of idealists and realists shaped the discussions. Even though the conferences could not always prevent the outbreak of new wars, they laid the foundation for today’s international courts and tribunals, such as the International Court of Justice, which has its seat in the Peace Palace. The Hague Conventions on the laws of war concluded in 1899 and 1907 contributed significantly to the evolution of what is modern international humanitarian law (IHL). And concepts on disarmament and arms control, multilateral negotiations and international organisations discussed then, returned in the twentieth century.